The Forgotten Drug of Abuse: How Junkies Grew Addicted to Talwin - The Atlantic

A history professor and researcher discovers old advertisements from the Sterling Drug Company in the Smithsonian's vast archives.

The Sterling Drug Company papers are held at the Smithsonian's off-site facility, which turns out to be a great thing: you get to go right into the "stacks" because there's no public reading room, and that means walking by noncommissioned items from the Museum of Natural History -- it seemed like every time I went I noticed a new rhinoceros or whale peeking out from behind a tarpaulin. I felt a little guilty because one of the archivists had to commute out to the facility every day and work at a makeshift table next to me, but she was cheerful good company and kept insisting that she didn't mind.

Sterling, a voracious grow-through-acquisitions drug company, ended up selling some of the early 20th century's most important medicines: aspirin; the sulfa drugs; neosalvarsan (the famed "magic bullet" for syphilis); the first barbiturate sedatives Veronal and Luminal; the first synthetic narcotic Demerol; and many more. The most significant of these drugs came into Sterling's possession during the World Wars, when the U.S. government confiscated the patents and sometimes even factories of German pharmaceutical houses and gave or auctioned them off to American companies.

Story continues below

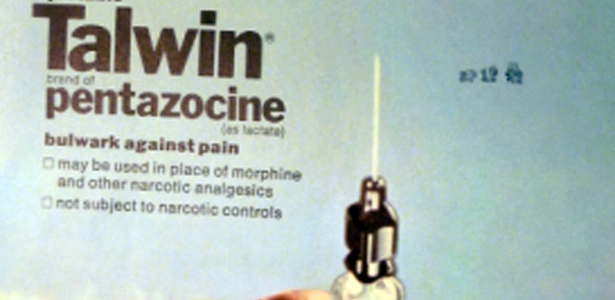

One particularly fascinating drug saga I tracked through the archive was the rise and fall of a narcotic (pain reliever) named Talwin. Talwin debuted with much ballyhoo in 1967 as the first non-addictive narcotic -- a holy grail of sorts for pharmaceuticals, and a discovery preceded by decades of dashed dreams. Sterling's ads weren't shy about the new miracle drug, as these examples show; note how they remind readers, repeatedly, that the drug requires no special narcotics licenses or prescription triplicates. Eventually, however, the occasional instances of abuse, dependence, and addiction grew into a genuine public health problem in Chicago and a few other cities by the late 1970s. As it turned out, the drug by itself was barely addictive, but, if crushed up with a common antihistamine (Pyribenzamine) and injected, it was a passable substitute for heroin -- something addicts were much desirous of in the late 1970s when prices had risen. Eventually Talwin was put on the Schedule of Controlled Substances after all.

The Sterling collection has plenty of interesting material, all of which is closely and, for the most part, accurately described in a 400-plus-page finding aid. Record Group 1, which I only peeked at, contains actual samples of Sterling Drug packaging, labels, products, and more. I spent most of my time in Record Groups 2 and 3, which contain marketing materials: medical journal advertisements (of course), and a wide range of mailings to physicians, from research-heavy booklets to lighthearted Madison Avenue gimmickry.

Record Group 4 includes material about the company, and there's a little something for everyone: for business historians there are many, many in-house newsletters from various aspects of the company (the factory, the sales force, etc.), which detail company life and corporate culture over the century. The annual reports to stock holders give a financial overview. Clipping files collect news coverage of the company. Unfortunately, there is nothing on corporate decision making, policy discussions, and the like.

Overall, however, there is much here of value to historians of pharmaceuticals, of the pharmaceutical industry, and of advertising.

Image: Sterling Drug Company.

This post also appears on the Smithsonian Collections Blog, an Atlantic partner site.

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.

Comments

Post a Comment